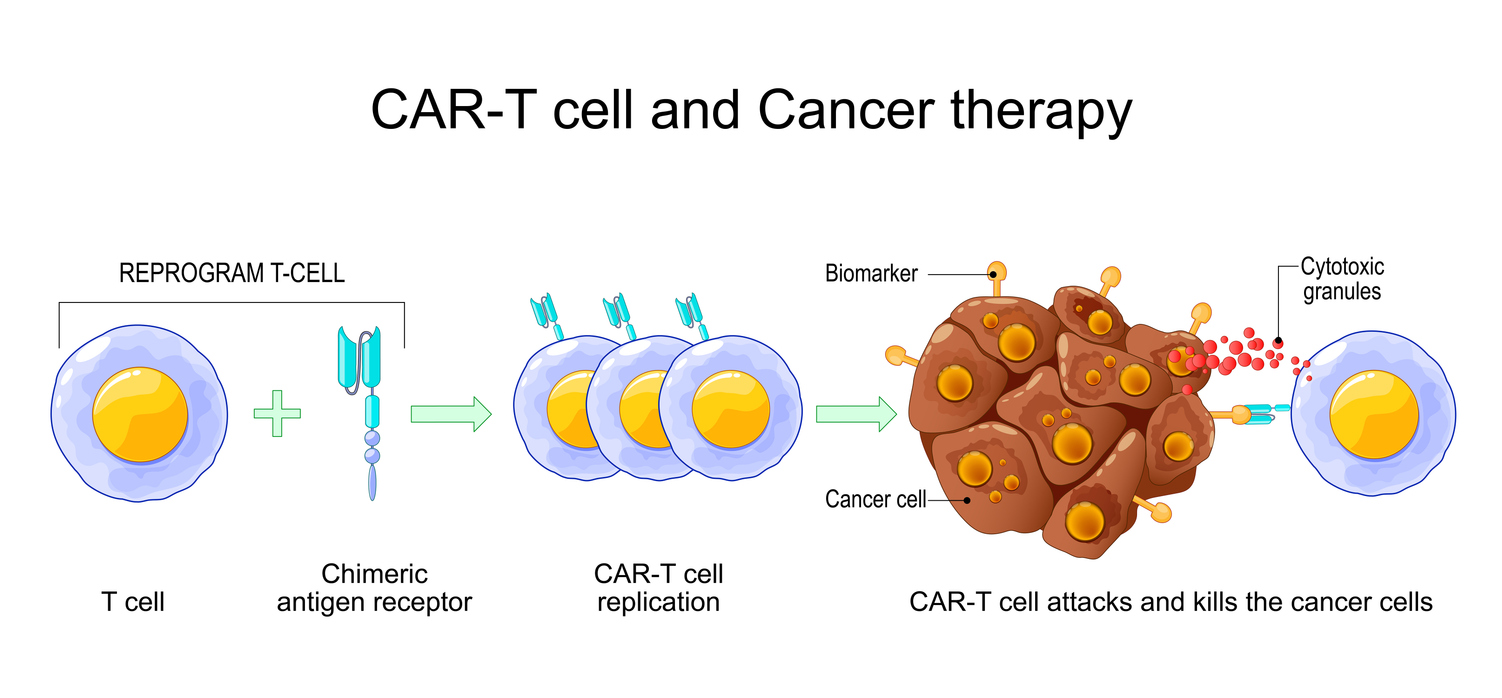

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of hematologic cancers, offering durable and often life-saving responses even in relapsed or refractory cases resistant to conventional treatments such as chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation [1]. CAR-T therapy works by genetically engineering a patient’s own T cells to express a synthetic receptor (CAR) that recognizes tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) on the surface of malignant cells. Upon reinfusion, these modified T cells are primed to seek out and destroy cancer cells with heightened specificity and potency, surpassing the natural immune response [1].

The most prominent successes of CAR-T therapy have been observed in hematologic malignancies, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), large B-cell lymphoma, and multiple myeloma, where durable remissions have been achieved even in patients with poor prognoses [2]. Regulatory approvals by agencies such as the FDA have cemented CAR-T’s place as a groundbreaking advancement in oncology [1]. Despite this success, CAR-T therapy faces significant challenges, including interpatient variability, complex manufacturing processes, and severe toxicities like cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity [1].

In parallel, CAR-Natural Killer (CAR-NK) cell therapies are emerging as a promising alternative, particularly for solid tumors where CAR-T has struggled. CAR-NK cells are engineered NK cells, part of the innate immune system, designed to express CARs that enhance their cytotoxic potential. Unlike T cells, NK cells can kill target cells without prior sensitization, making them naturally cytotoxic and less dependent on the tumor microenvironment (TME). Importantly, CAR-NK therapies carry a lower risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), making them amenable to allogeneic (donor-derived) approaches. This opens doors for off-the-shelf, universal CAR therapies that could bypass some of the logistical and manufacturing hurdles faced by autologous CAR-T treatments [1].

However, both CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies encounter barriers, such as limited persistence, poor tumor infiltration, immune escape, and the development of severe side effects. These challenges highlight the urgent need for robust biomarker strategies to optimize therapeutic efficacy, ensure safety, and improve the scalability of manufacturing and delivery.

Biomarkers play a crucial role in addressing the multifaceted challenges in CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies. They provide insights into treatment efficacy, safety, and manufacturing optimization by serving as indicators of immune activation, persistence, toxicity, and tumor response. By understanding these markers, researchers and clinicians can explore new research avenues, predict patient responses, minimize adverse effects, and refine treatment protocols. For example, Interleukin 12 (IL-12) enhances Th1 differentiation and boosts cytotoxic functions in T and NK cells. Armored CAR-T cells engineered to secrete IL-12 show superior tumor-killing abilities in preclinical models, particularly against solid tumors [1]. However, systemic IL-12 can cause severe inflammation, requiring careful delivery approaches, such as localized or inducible expression systems. Another example is Interleukin 15. When delivered as an IL-15/IL-15Ra complex, its biological potency is enhanced, resulting in prolonged CAR-NK cell persistence, enhanced cytotoxicity, and reduced exhaustion [1].

The table below explores some of these biomarkers’ roles in the therapeutic process and related toxicities, offering insights into how they can inform the ongoing development of CAR-based therapies.

| Biomarker | Mechanistic Role | Efficacy Contribution | Toxicity Association | Research Insights |

| IL-2 | Supports T cell proliferation, survival, and activation. | Enhances CAR-T expansion and persistence post-infusion. | Elevated IL-2 is linked to Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS). | IL-2 is a strong cytokine that promotes T cell growth and function. It is commonly added to CAR-T cell cultures [3]. High IL-2 levels can also activate macrophages and other immune cells, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and IL-1, which contribute to CRS [4]. |

| IL-12 | Promotes Th1 differentiation, boost cytotoxicity | IL-12 secretion by CAR-T cells can improve tumor killing by promoting a pro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment and recruiting innate immune cells. | High Systemic IL-12 can drive inflammation, organ toxicity | Armored CAR-T cells engineering to secrete IL-12 show enhanced tumor killing ability [5]. Systemic expression of IL-12 by CAR-T cells has been associated with severe toxicities, including CRS and organ damage [6]. |

| IL-15 | Sustains NK cell and memory T cell populations, promotes homeostatic proliferation | Critical for CAR-NK cell persistence and long-term activity | Safety switches such as Inducible caspase 9 (IC9) helps mitigate CRS risk in IL-15 CAR-based therapies. | Co-expressing IL-15 with its receptor (IL-15/IL-15Rα) in CAR-NK-92 cells significantly enhances their proliferation, cytokine secretion, and cytotoxicity against B-cell leukemia in vitro and in vivo [7]. |

| IL-17A | Promotes proinflammatory signaling, enhances immune cell tumor infiltration | Increases immune infiltration and enhances solid tumor targeting | Excessive IL-17A may drive autoimmunity, tissue inflammation | Blocking IL-17A with secukinumab eliminated the cytotoxic function of C3aR-modified CAR-T cells, indicating that IL-17A and Th17 cells are crucial for tumor elimination [8] |

| MCP-1 | Recruits monocytes and macrophages to sites of inflammtion | May promote beneficial myeloid recruitment to the tumor microenvironment | Linked to early CRS and neurotoxicity | A recent study suggests that MCP-1 signaling via CCR3 plays a role in CAR-T-associated neurotoxicity and may serve as an early biomarker and therapeutic target [9]. |

| MIP-1a | Attracts macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes | Support local immune activation and cell recruitment | Guides preemptive management of neurotoxicity | Elevated MIP-1a levels associated with neurotoxicity in CAR-T patients [10]. |

| VEGF | Controls angiogenesis and shapes tumor vasculature | VEGF inhibition can improve CAR cell infiltration | High VEGF may create immune-excluded environments | VEGF blockade shown to synergise with CAR therapies in preclinical models [11]. |

Biomarkers play essential roles in optimizing the manufacturing and clinical delivery of CAR-based therapies by providing insights into product quality, immune function, and patient response. During manufacturing, biomarkers such as IL-2 can be used to evaluate T-cell activation and proliferation. Elevated IL-2 levels may indicate successful stimulation and expansion of CAR-T cells, a critical step for ensuring sufficient therapeutic doses.

Together, these biomarkers enable robust quality control during manufacturing and informed clinical decisions post-infusion. By tailoring therapy to the biological signals from both the CAR product and the patient, biomarkers help ensure safer, more consistent, and more effective CAR-based treatments.

Advanced biomarker-guided strategies are pivotal in optimizing CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies, ensuring a balance between efficacy and safety, and refining manufacturing pipelines. Cytokines and chemokines are not just molecular markers but active participants in shaping therapeutic outcomes. As ongoing preclinical studies and trials expand, leveraging these biomarkers will be central to the next generation of precision-engineered cell therapies.

References:

- Zhang et al., (2022), “CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematological Malignancies: Current Opportunities and Challenges”, Front Immunol., 13:927153, DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.927153

- Zhou et al., (2024), “CAR-T cell combination therapies in hematologic malignancies”, Exp Hematol Oncol., 13(1):69, DOI: 10.1186/s40164-024-00536-0

- Jafarzadeh, et al., (2020), “Prolonged Persistence of Chimeric Antigen Receptor(CAR) T Cell in Adoptive Cancer Immunotherapy: Challenges and Ways Forward”, Front Immunol., 11:702, DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.00702

- Xiao et al., (2021), “Mechanisms of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity of CAR-T therapy and associated prevention and management strategies”, J Exp Clin Cancer Res., 40(1):367, DOI: 10.1186/s13046-021-02148-6

- Liu et al., (2019), “Armored Inducible Expression of IL-12 Enhances Antitumor Activity of Glypican-3-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineering T Cells in Hepatocellular Carcinoma”, J. Immunol., 203(1):198, DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800033

- Zhang et al., (2015), “Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered with an inducible gene encoding interleukin-12 for the immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma”, Clin Cancer Res., 21(10):2278, DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2085

- Silvestre et al., (2023), “Engineering NK-CAR.19 cells with the IL-15/IL-15Ra complex improved proliferation and anti-tumor effect in vivo”, Front Immunol., 14:1226518, DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1226518

- Lai et al., (2022), “C3aR costimulation enhances the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy through Th17 expansion and memory T cell induction”, J Hematol Oncol., 15(1):68, DOI: 10.1186/s13045-022-01288-2

- Geraghty et al., (2025), “Immunotherapy-related cognitive impairment after CAR-T cell therapy in mice”, Cell, 10.1016/j.cell.2025.03041

- Teachey et al., (2016), “Identification of Predicative Biomarkers for Cytokine Release Syndrome after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia”, Cancer Discov., 6(6):664, DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0040

- Wu, S. et al., (2025), “Inhibition of VEGF signaling prevents exhaustion and enhances anti-leukemia efficacy of CAR-T cells via Wnt/ β-catenin pathway”, J. Transl Med., 23(1):494, DOI: 10.1186/s12967-025-05907-z